Threat Without Borders Newsletter - SE

Special Edition - Stylometry for Investigators, Part 3

Before computers (yes, investigations occurred before computers), investigators studied writing styles by carefully reading and manually counting features. This fundamental approach remains effective. Manual analysis helps develop an intuition for writing patterns that software tools might overlook. It allows you to read the text as a human while analyzing it scientifically.

Begin by reading both the questioned document and known samples multiple times. Start with content—what are they saying? Then examine style—how do they say it? On the third read, focus on identifying specific patterns. Repeated reading builds familiarity and helps you spot subtle consistencies.

Create a simple observation framework. Look for patterns that consistently appear in the known samples and see if they match or differ in the questioned document. Think of yourself as a detective gathering evidence—each stylistic feature could be a clue.

You can manually extract key stylometric features through basic counting and simple calculations. Here’s what to focus on and how to do it effectively:

Function Word Frequency

This is where manual analysis truly excels because you can observe these patterns as you read. Focus on the most common function words: “the,” “and,” “of,” “to,” “in,” “a,” “for,” “is,” “on,” “that,” “with,” “as,” “but,” “by,” “at.” Count how often each appears in a 500-word sample from each text. You can do this with the find function in any word processor, search for “ the “ (with spaces), and count the hits. Divide by the total word count to determine the frequency per hundred words. So, if “the” appears thirty times in 500 words, that equals 6.0 per hundred words.

Create a simple table comparing these frequencies across texts. You’re seeking similar patterns. For example, if the suspect uses “the” 6.2 times per hundred words and “of” 3.8 times per hundred words, and the questioned document shows 6.0 and 3.9, that’s comparable. If the questioned document shows 4.1 and 5.6, that’s different.

Pay close attention to word pairs where writers make choices. For instance, “different from” versus “different than,” “try to” versus “try and,” “between” versus “among,” “while” versus “whilst.” Search for these phrases in all your samples and see if the preferred pattern matches.

Punctuation Habits

Count punctuation marks in the same 500-word samples you’re analyzing for other features. How many commas appear per hundred words? How many periods, semicolons, dashes, exclamation points? These are easy to count and remarkably consistent within an author’s work.

Focus on comma placement specifically. Some writers use commas before “and” in lists (the Oxford comma); others don’t. Some writers put commas after introductory phrases consistently; others are sporadic. Read through the samples, looking for these micro-patterns. They’re unconscious habits that reveal the writer’s identity.

Check for semicolon usage. Many writers never use semicolons; others use them regularly. If your suspect has never used semicolons in thousands of words of known writing and your questioned document contains several, that’s significant. If both use semicolons at similar frequencies, that’s evidence of similarity.

Contraction Patterns

Count contractions: “don’t,” “can’t,” “won’t,” “it’s,” “I’m,” “you’re.” How many appear per hundred words? More importantly, which ones appear? Some writers contract everything; others contract selectively; some avoid contractions entirely.

Look for specific patterns. Does the writer use “cannot” or “can not” when they choose not to contract? Do they write “it is” or “it’s”? These small choices create distinctive patterns. Make a list of every instance where the writer could have used a contraction but didn’t, or did use one. The pattern reveals preference.

Vocabulary Complexity

This is more difficult to measure by hand but still noticeable. As you read, highlight words that are unusual or sophisticated. In a 500-word sample, how many words are considered advanced vocabulary compared to common everyday words? You can roughly estimate the type-token ratio by counting unique words in a sample. Take the first 100 words of each text and count how many different words appear. Someone who uses ninety different words in those 100 has a higher vocabulary diversity than someone who uses only sixty different words. While it takes time to count manually, it reveals real differences. Observe word choice patterns. Does the writer say “use” or “utilize”? “Help” or “assist”? “Buy” or “purchase”? Consistent preference for simpler or more complex alternatives shows style.

Opening and Closing Patterns

How do sentences begin? Count the first word of twenty consecutive sentences. How many start with “The”? How many start with “A” or “An”? How many start with conjunctions like “And” or “But” (which some writers avoid)? How many start with participial phrases ending in “-ing”?

These patterns are easier to spot than to count. As you read, you develop a sense of whether this writer favors certain sentence openings. If your suspect frequently starts sentences with “However,” and the questioned document never does, that’s observable without sophisticated statistics.

Look at paragraph structure too. Does the writer favor short paragraphs with two or three sentences, or longer paragraphs with six or eight sentences? Do they use single-sentence paragraphs for emphasis? This visual structure creates recognizable patterns.

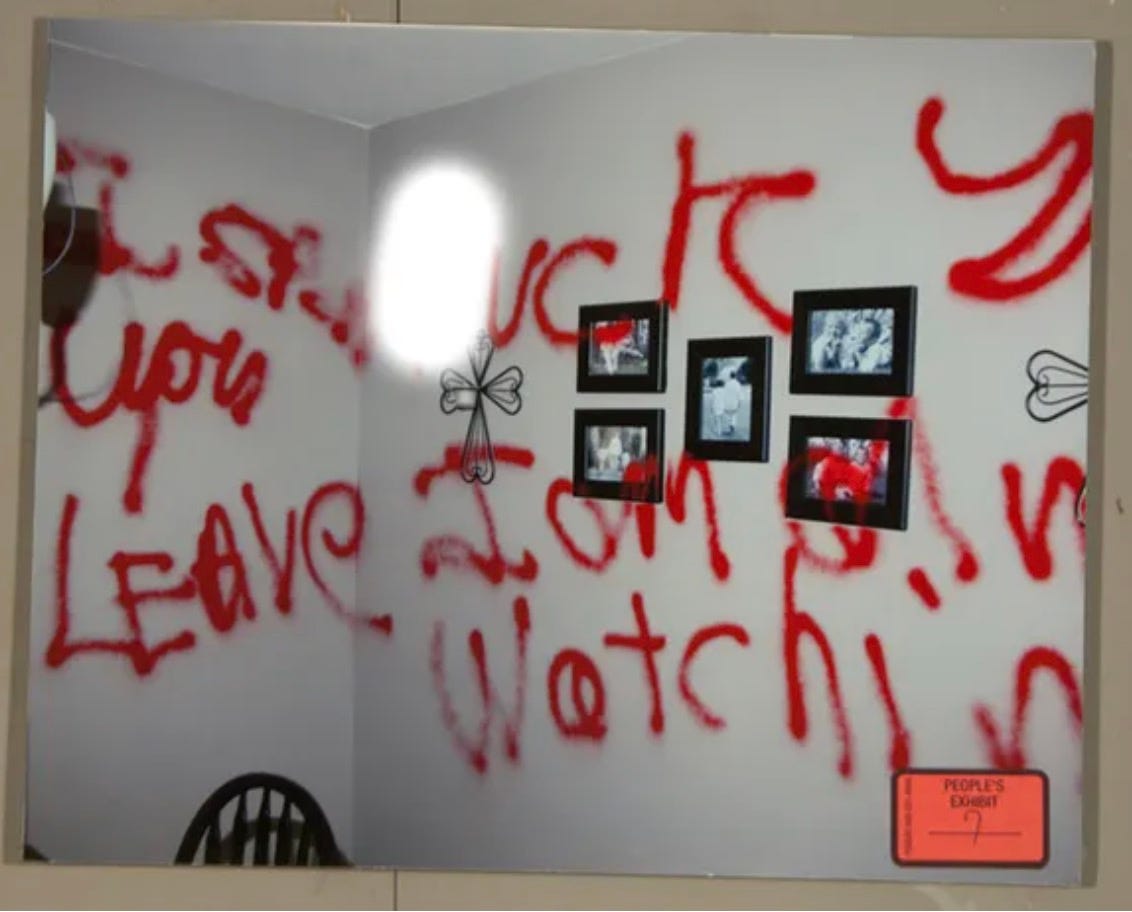

A notable example of stylometry’s forensic use is the 2011 case involving Christopher Coleman, a security chief at Joyce Meyer Ministries who murdered his wife and two sons in Illinois. In the two years before the murders, Coleman claimed to have received threatening messages supposedly from a stalker upset about his work with a televangelist, and threats were spray-painted at the crime scene.

Forensic linguists analyzed the anonymous threats and compared them to Coleman’s writing, finding distinct linguistic features such as repeated phrases, unique syntactic structures, and peculiar word choices that indicated Coleman was likely the author of the threats. This linguistic evidence was key in showing that Coleman had fabricated the stalker story to serve as an alibi and mislead investigators. Along with digital and physical evidence, it helped verify his guilt.

The case illustrates how stylometric analysis, when integrated into a thorough investigation, can yield scientifically sound evidence to identify authors and expose deliberate deception in criminal cases.

Some additional tips to link writings:

Look for signature phrases: Every writer has expressions they favor. It might be “at the end of the day,” “to be fair,” “the fact of the matter,” or any of hundreds of common phrases. Search manually through all your collected texts looking for these. If multiple accounts use the same unusual phrase repeatedly, that’s a strong indicator of common authorship.

Track punctuation quirks: Does the writer use ellipses frequently...like this? Do they favor dashes--like this--for asides? Do they put spaces before punctuation marks , like this? These quirks are easy to spot manually and often persist even when writers try to maintain different personas.

Notice capitalization in informal writing: On platforms like Twitter or Reddit, some people maintain standard capitalization, others write in all lowercase, and some Use Capitals For Emphasis Oddly. These habits are consistent and observable. If your anonymous account and your suspect both show the same unconventional capitalization patterns, that’s evidence.

Compare topic-handling approaches: When different accounts discuss the same topic, do they make similar points with similar phrasing? Do they share the same biases or knowledge gaps? Content overlap is different from stylistic analysis, but it corroborates stylometric findings.

Next week, we will conclude this series by examining how AI influences the application of stylometry in linking writings.